There does not appear to be any metric by which we could argue that our current socioeconomic systems are sustainable. Despite this, we delude ourselves into believing that business as usual can continue indefinitely.

We assist ourselves in this art of self-delusion by failing to ask the right questions or simply limiting the information that we are willing to consider. The recently released Australian Energy Resource Assessment (AERA), particularly the aspects related to oil, is yet another example of how our government, and the bureaucracies supporting it, are failing to ask the right questions. The unfortunate consequences of this approach imply that Australia will be left with few options to respond to a very challenging set of problems, something that could and should be avoidable.

It should be noted that most of the information in Chapter three, “Oil”, of the AERA is good, particularly the assessment of Australia’s future oil production. To the lay person it would appear to be a thorough and accurate appraisal of Australia’s oil situation. The problem’s lie in the nuances, the fallacies, the assumptions and the reliance on a narrow and far from fool proof set of data and projections on the international oil arena. These shortfalls could have significant implications for Australia, so let’s take a closer look.

Advertisement

World oil reserves and the R/P fallacy

The AERA confidently asserts that the world has 1,408 billion barrels of proven reserves. This data is sourced from BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy 2009. The statistical review is viewed as an energy bible by many, yet BP is so confident about this publication that it won’t even respond to questions about the data contained therein. The reason being that the information contained therein is not audited and of varying degrees of accuracy.

The best example is provided by the 300 billion barrel jump in OPEC oil reserves during the 1980s. For example, Saudi Arabia’s oil reserves jumped from 170 billion barrels in 1987 to 255 billion barrels in 1988 and have remained at just over 260 billion barrels ever since. This story is repeated among most of the OPEC nations. So what happened in the 1980s. Was there a wave of new discoveries? The answer is no. But what we know did happen is that OPEC introduced a production quota system based upon oil reserves. So maybe, just maybe, some of these “reserves” are political numbers used to enhance the production quota of a nation. If this is the case, some 250 to 300 billion barrels, around a fifth of the worlds proven oil reserves may be paper barrels only.

We then move onto the Reserves/Production ratio, a simple calculation that suggests that there is 42 years worth of oil left at current production rates. The AERA quotes the International Energy Agency suggesting that oil production will increase at one per cent per annum out to 2030. This projection would see current reserves exhausted by 2047, only 37 years time. Subtracting $250 billion barrels of OPEC’s political reserves would see reserves exhausted by 2040, only 30 years time. Raise the growth in production to 2 per cent per annum and the oil age is potentially over by 2037. These figures are of course nonsense, oil will never run out entirely. We know this because the production profile of oilfields and oil regions roughly approximates a bell curve. Oil doesn’t run out, as the pressure drops each field just produces less and less until it reaches a point where it is not economically viable. So this is good news, we will still have oil for many decades (or centuries?) to come, it is just that the flow will not be the 80 odd million barrels a day that we currently produce and the global economy has come to depend upon.

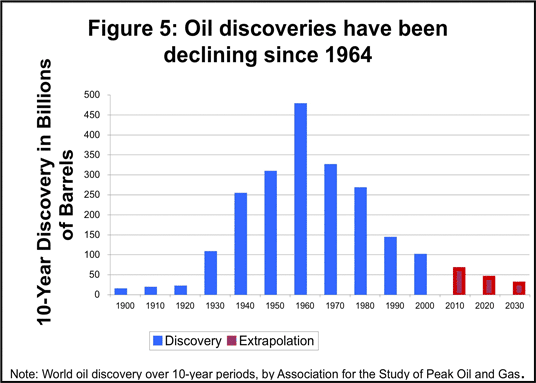

The AERA gets around this little problem by suggesting that new oil discoveries and reserves growth could offset the problem of declining reserves and production levels (p48). A very strong argument could be mounted to suggest that this is highly unlikely to occur. Despite significant technological advances, oil discoveries have been in long term decline for more than 40 years as shown in the chart.

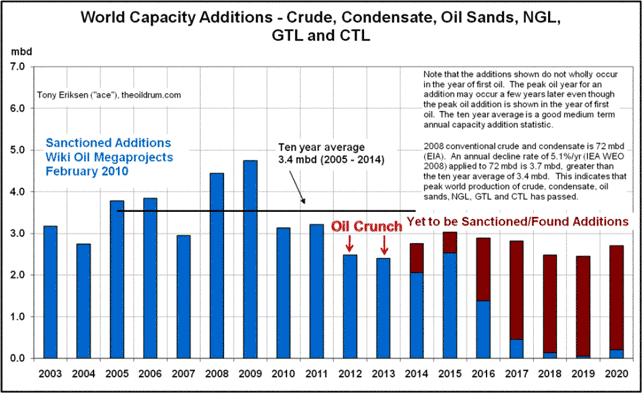

The depletion rate from existing oil fields is somewhere in the order of 4.5 - 6 per cent per annum, a figure that will continue to increase. Combining these factors, and the projects scheduled to come on line over the next few years (see chart below), it becomes obvious that world oil production is unlikely to grow much, if at all in coming decades, indeed the opposite is more likely the case. And this does not consider the many and varied geopolitical influences that could result in reduced production levels.

Advertisement

Source: The Energy Bulletin

For some reason however the AERA does not detail these factors anywhere in its analysis. Unfortunately this is not the only gap in the AREA.

Discuss in our Forums

See what other readers are saying about this article!

Click here to read & post comments.

35 posts so far.