The projection that Australia’s population will grow to 36 million by 2050, contained in the 2010 Intergenerational Report, was received very differently by Australian governments and the community.

Many Australians are deeply uncomfortable with rapid population growth. A recent poll (PDF 108KB) found that 48 per cent of Australians thought such growth would be bad for Australia, while only 24 per cent thought it would be good. They intuit, perhaps, that governments might not be up to the task of providing sustainable water, energy and transport infrastructure for rapidly growing cities.

The Government’s stance has vacillated between claiming that such rapid population growth is inevitable on the one hand, and assuring us that it is good for Australia on the other.

Advertisement

The claim of inevitability is disingenuous and easily dismissed. While some degree of growth is inevitable over the next few decades, both the pace of growth and the ultimate trajectory are well within the government’s power to influence. Migration is the largest determinant of long-term population growth for Australia, and different migration levels mean the difference between population stabilisation and ongoing rapid growth.

More interesting, and more forthright, is the claim that rapid population growth is in Australia’s best interest. Finance Minister Lindsay Tanner has been the government’s most vocal proponent of the “Big Australia” preference. In a recent piece, Tanner asked “Do we want lower productivity and less economic growth?”, implying that lower population growth could only damage our economy.

Is there good evidence for or against a link between population growth and economic prosperity? Tanner unfortunately offered none in support of his argument for rapid growth. One’s view on the question depends largely on an assessment of so-called “economies of scale” and “diseconomies of scale”.

Economies of scale are things that get better the more of us there are - greater diversity of restaurants is an example that rings true for me.

Diseconomies of scale are things that get harder the more of us there are. For example, water supply tends to get more expensive per unit as population increases, as increasing supply requires resorting to progressively more distant and difficult to access sources. A desalination plant is more expensive than extraction from local wells, for example. Congestion is another diseconomy of scale, and greenhouse pollution is rapidly emerging as another.

Economic modelling conducted for the Intergenerational Report concluded that lower population growth would mean lower per-capita GDP for Australia, among other ills. But a closer look reveals some flaws. For one, the modelling excluded any environmental parameters, such as the potential impact of a larger population on greenhouse pollution, water use, and congestion. The omission seems all the more glaring when you consider that climate change was identified as one of the two most important intergenerational challenges facing Australia today. In effect, the Intergenerational Report included many potential economies of scale, while excluding the most important diseconomies of scale. The result tells us more about the modeller than about what is likely to happen in the real world.

Advertisement

The most considered and balanced treatment of this issue in recent times is the final report of the National Population Council, an official Commonwealth body, released in 1991. Although nearly two decades old now, its analysis remains compelling and relevant. It is not, I should stress, an “anti-growth” document.

On the link between population and economy, the Council found that the jury was still out: “because of our limited present direct knowledge of economies and diseconomies of scale, it is not possible to state … that population growth per se enhances or reduces the productivity basis for economic progress.”

Unfortunately, our knowledge of economies and diseconomies of scale is no better today than it was back then. This leaves Tanner’s claim that we’d be less prosperous if we don’t grow our population on a pretty shaky theoretical base.

But enough of economic models, what about the real world? The Intergenerational Report discusses just two examples: Italy and Japan. Both nations have experienced very low fertility levels, rapidly ageing populations, and slow economic growth in recent decades. On the basis of these two countries, the Intergenerational Report concludes that “A key lesson from the international experience is that countries with low population growth or declining populations such as Japan and Italy face lower potential rates of economic growth than countries with relatively healthier population growth.”

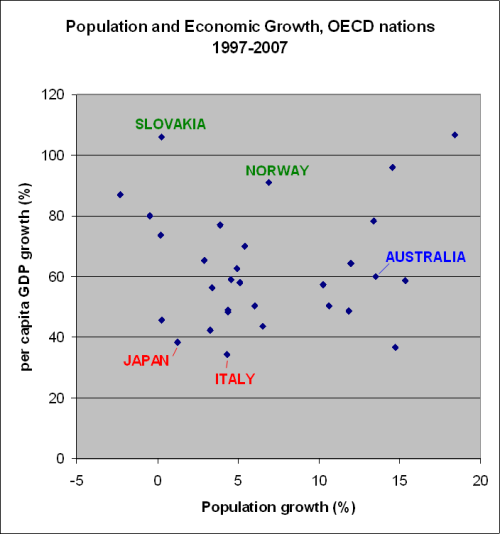

But why focus on those two countries? A broader look across the OECD (see figure 1) shows that rapid population growth is neither necessary nor sufficient to achieve solid per capita GDP growth. (I leave aside here the question of whether per capita GDP growth is a useful goal to strive for, except to say that Joseph Stiglitz and many other mainstream economists have cast doubt on the wisdom of an excessive focus on GDP.)

In fact, no fewer than 11 OECD nations achieved faster per-capita economic growth than Australia from 1997-2007, despite slower population growth or even in some cases no population growth or a slight decline.

Clearly enough, experience shows us that rapid population growth is no guarantee of economic prosperity, and conversely a stable population does not doom a country to economic failure.

The real puzzle here is why the Intergenerational Report discusses only the two worst performing countries among OECD nations on this issue, rather than looking at some of the success stories. Norway looks like an interesting case - thriving economy, despite an ageing population and much lower population growth than Australia. Or how about Slovakia, with a stable and ageing population and a booming economy?

The Netherlands, the Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Finland … with so many intriguing examples of countries with stable or low-growth populations that somehow continue to enjoy vibrant economies, it’s a pity the report didn’t take a more lateral approach.

As for the significant environmental, planning and social challenges of population growth, the report acknowledges them but plays them down in a single line of optimism: “The risks in these areas are manageable provided governments take early action to plan for future needs.” Sure, but that’s a pretty big proviso. It’s a bit like saying I can win a marathon, provided I run really fast: technically true, but it really begs the question of how.

Lindsay Tanner similarly suggests that we focus on better planning and less profligacy, rather than worrying about population. One can hardly argue against better planning and lower ecological footprints; they are desperately needed. What is beyond me is how he can be so sanguine about our ability to achieve those ambitious goals, in the face of all evidence that we’re nowhere close to the trajectories required even to reduce the ecological footprint of the present population.

The truth is we are struggling just to catch up with the huge backlog of infrastructure, social and environmental investments for our 22 million people, let alone the 36 million that would present if we continued current migration trends.

A better approach, again, is that provided by the National Population Council in 1991. It said that “Solutions should not be assumed for population-related problems through other policies, unless the institutional and other mechanisms required to effectively implement those solutions are in place”.

The assumption that the impacts of population growth will be defrayed by technological and planning improvements is the opposite of a precautionary approach. It is fine to hope for the best possible outcome, but reckless to pursue policies that will increase our population on the expectation that the best possible outcome will occur. And even more reckless in the face of the facts are that Australia’s per-capita greenhouse pollution continues to increase year on year, our cities continue to push beyond urban growth boundaries, and few of the policies or practices that would signal a transition to a genuinely sustainable lifestyle are in place.

In the end we as a nation have options about our future population. The Intergenerational Report and the government treat us as if we have none, confronting us with a false choice between rapid population growth or economic calamity. The truth is that we can care for an ageing population, enjoy economic prosperity and work towards ecological sustainability without rapid population growth. How? Just ask the Norwegians. Or the Slovaks. Or the Dutch. Or …