So the price of electricity for all consumers is raised. Call it what you will, the taxpayer is contributing significantly to intermittent energy, and propping it up, with a cost estimated at around $2.8 Billion. Electricity consumers pay this cost, and those of them who aren’t taxpayers are likely to be retirees, unemployed, or in some other way involuntarily out of the workforce.

Claim 3: Privatisation is the problem

Professor Quiggin makes that claim a number of times, including around 2:15:00. He says the rate of return on the network is too high, and that is because it is set in the context of privatisation. There is a major problem with this. The network in Queensland is owned by the government, so “nationalisation” is already in place, and there is nothing to stop the state charging a lower rate than the cap set by the Australian Energy Regulator.

Professor Quiggin claims the appropriate rate of return on the network should be the government bond rate. That is nonsensical. The government bond rate is the rate at which the government borrows. If the network return was that rate there would be no profit to the government and no cover for the risk they would be taking in providing the network. It would also discourage investment in the network as the government would be likely to get better returns elsewhere.

Advertisement

On top of that it would be an effective subsidy to business customers, even if you consider the provision of “at cost” electricity to the householder as welfare. It would also push government borrowing higher, and making it more difficult to borrow for other assets which private markets can’t provide, and increasing borrowing costs at the same time as state debt became riskier.

It also ignores the problem that the government has a conflict of interest. Not only are governments unlikely to take the same return on the network as it costs them to borrow, but as a monopoly provider they are likely to pad costs. One of the problems with the way we regulate networks is that it is done on a rate of return plus costs basis. The regulator not only allows the networks to recover capital costs, but it also allows them to recover all their administrative and maintenance costs as well. So there is no incentive to run lean and mean with staff.

At around 2:15:00 Professor Quiggin says he’d accept privatisation if the private companies would accept the government bond rate as their rate of return. So, while he accepts the principal of privatisation, in practice his model would have no investors. But it is an interesting concession.

It is hard to square Professor Quiggin’s position on rates of return with his support for the renewables industry. He cheers on the demise of coal-fired power stations, owned by the state, but these are being replaced by windmills and solar panels owned by the private sector, and also by batteries and other storage devices, also owned by the private sector.

For the state government, as far as power generation is concerned, privatisation of generation is the preferred means to decarbonise, about which Professor Quiggin appears to have nothing to say.

Final note: Do more intermittent renewables really mean more expensive power?

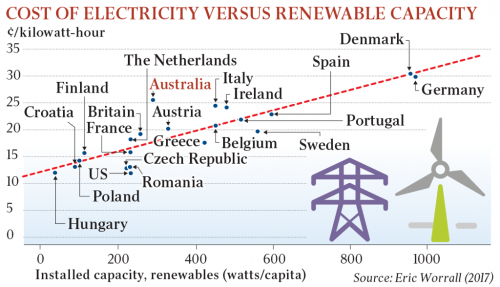

As explained earlier, the costs of intermittents are hidden and relate to backup and reliability and it is easy to invent reasons for power increases, such as “It’s a problem with how we regulate the network”. What the graph below does is to strip out the irrelevant by demonstrating that in the real world there is a direct relationship. It’s impossible to argue with this, although it should be noted that Australia performs worse than most, so there are compounding factors here as well.

Advertisement

Discuss in our Forums

See what other readers are saying about this article!

Click here to read & post comments.

30 posts so far.